Translate

Monday, October 5, 2020

How Facebook and Twitter Handled Trump’s ‘Don’t Be Afraid of Covid’ Post

from NYT > Technology https://ift.tt/3iDf82C

via A.I .Kung Fu

Apple removed headphones and speakers from Bose, Logitech, and Sonos from its online store at the end of Sept., asked retail employees to do the same (Mark Gurman/Bloomberg)

Mark Gurman / Bloomberg:

Apple removed headphones and speakers from Bose, Logitech, and Sonos from its online store at the end of Sept., asked retail employees to do the same — - Apple is working on first over-ear headphones, smaller HomePod — Products from Sonos, Bose, Logitech pulled from online store

from Techmeme https://ift.tt/34qLnNA

via A.I .Kung Fu

A US District Judge ordered Cisco to pay $1.9B to Virginia-based Centripetal Networks for infringing four cybersecurity patents; Cisco says it will appeal (Allison Levitsky/Silicon Valley ...)

Allison Levitsky / Silicon Valley Business Journal:

A US District Judge ordered Cisco to pay $1.9B to Virginia-based Centripetal Networks for infringing four cybersecurity patents; Cisco says it will appeal — Cisco Systems Inc. was hit Monday with a $1.9 billion judgment in a 2018 patent infringement suit filed by Centripetal Networks, a small cybersecurity firm in Virginia.

from Techmeme https://ift.tt/3nnBmJq

via A.I .Kung Fu

Uncle Sam Is Looking for Recruits—Over Twitch

from Wired https://ift.tt/2GpenwY

via A.I .Kung Fu

Xbox Has Always Chased Power. That's Not Enough Anymore

from Wired https://ift.tt/34oECMe

via A.I .Kung Fu

A Common Plant Virus Is an Unlikely Ally in the War on Cancer

from Wired https://ift.tt/3ixA62W

via A.I .Kung Fu

The Secret History of Video Game Music's Female Pioneers

from Wired https://ift.tt/33w8gjn

via A.I .Kung Fu

The Turmoil Over ‘Black Lives Matter’ and Political Speech at Coinbase

from Wired https://ift.tt/3d24zEZ

via A.I .Kung Fu

The Women Who Invented Video Game Music

from Wired https://ift.tt/2SsJryq

via A.I .Kung Fu

Twitch Support Groups Are an Unlikely Source of Solace

from Wired https://ift.tt/3cZMveJ

via A.I .Kung Fu

7 Best Desktop PCs for Gaming (2020): Compact, Custom, Cheap

from Wired https://ift.tt/2ZScixd

via A.I .Kung Fu

US no longer sets the agenda for the internet, as 80%+ of users are now outside the US, and China has more smartphone users than US and western Europe combined (Benedict Evans)

Benedict Evans:

US no longer sets the agenda for the internet, as 80%+ of users are now outside the US, and China has more smartphone users than US and western Europe combined — When Netscape launched in 1994 and kicked off the consumer internet, there were maybe 100m PCs on earth, and over half of them were in the USA.

from Techmeme https://ift.tt/3nirO2y

via A.I .Kung Fu

Thank you for posting: Smoking’s lessons for regulating social media

Day by day, the evidence is mounting that Facebook is bad for society. Last week Channel 4 News in London tracked down Black Americans in Wisconsin who were targeted by President Trump’s 2016 campaign with negative advertising about Hillary Clinton—“deterrence” operations to suppress their vote.

A few weeks ago, meanwhile, I was included in a discussion organized by the Computer History Museum, called Decoding the Election. A fellow panelist, Hillary Clinton’s former campaign manager Robby Mook, described how Facebook worked closely with the Trump campaign. Mook refused to have Facebook staff embedded inside Clinton’s campaign because it did not seem ethical, while Trump’s team welcomed the opportunity to have an insider turn the knobs on the social network’s targeted advertising.

Taken together, these two pieces of information are damning for the future of American democracy; Trump’s team openly marked 3.5 million Black Americans for deterrence in their data set, while Facebook’s own staff aided voter suppression efforts. As Siva Vaidhyanathan, the author of Anti-Social Media, has said for years: “The problem with Facebook is Facebook.”

While research and reports from academics, civil society, and the media have long made these claims, regulation has not yet come to pass. But at the end of September, Facebook’s former director of monetization, Tim Kendall, gave testimony before Congress that suggested a new way to look at the site’s deleterious effects on democracy. He outlined Facebook’s twin objectives: making itself profitable and trying to control a growing mess of misinformation and conspiracy. Kendall compared social media to the tobacco industry. Both have focused on increasing the capacity for addiction. “Allowing for misinformation, conspiracy theories, and fake news to flourish were like Big Tobacco’s bronchodilators, which allowed the cigarette smoke to cover more surface area of the lungs,” he said.

The comparison is more than metaphorical. It’s a framework for thinking about how public opinion needs to shift so that the true costs of misinformation can be measured and policy can be changed.

Personal choices, public dangers

It might seem inevitable today, but regulating the tobacco industry was not an obvious choice to policymakers in the 1980s and 1990s, when they struggled with the notion that it was an individual’s choice to smoke. Instead, a broad public campaign to address the dangers of secondhand smoke is what finally broke the industry’s heavy reliance on the myth of smoking as a personal freedom. It wasn’t enough to suggest that smoking causes lung disease and cancer, because those were personal ailments—an individual’s choice. But secondhand smoke? That showed how those individual choices could harm other people.

Epidemiologists have long studied the ways in which smoking endangers public health, and detailed the increased costs from smoking cessation programs, public education, and enforcement of smoke-free spaces. To achieve policy change, researchers and advocates had to demonstrate that the cost of doing nothing was quantifiable in lost productivity, sick time, educational programs, supplementary insurance, and even hard infrastructure expenses such as ventilation and alarm systems. If these externalities hadn’t been acknowledged, perhaps we’d still be coughing in smoke-filled workplaces, planes, and restaurants.

And, like secondhand smoke, misinformation damages the quality of public life. Every conspiracy theory, every propaganda or disinformation campaign, affects people—and the expense of not responding can grow exponentially over time. Since the 2016 US election, newsrooms, technology companies, civil society organizations, politicians, educators, and researchers have been working to quarantine the viral spread of misinformation. The true costs have been passed on to them, and to the everyday folks who rely on social media to get news and information.

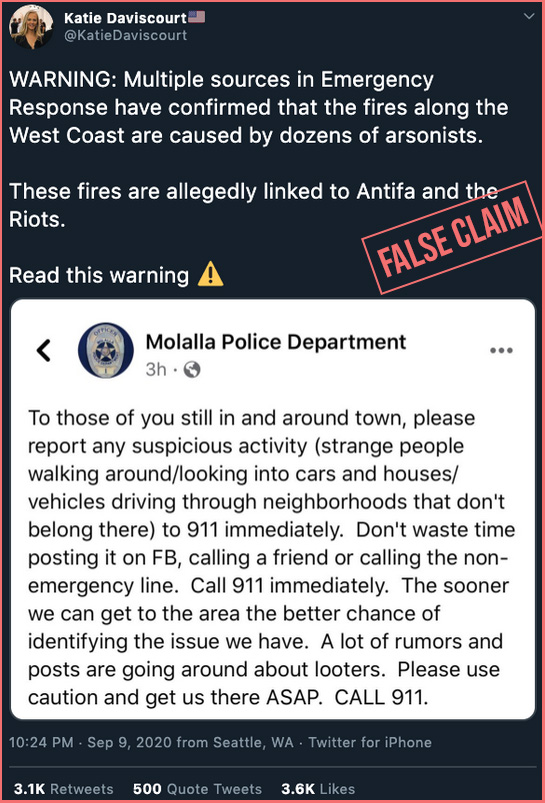

Take, for example, the recent falsehood that antifa activists are lighting the wildfires on the West Coast. This began with a small local rumor repeated by a police captain during a public meeting on Zoom. That rumor then began to spread through conspiracy networks on the web and social media. It reached critical mass days later after several right-wing influencers and blogs picked up the story. From there, different forms of media manipulation drove the narrative, including an antifa parody account claiming responsibility for the fires. Law enforcement had to correct the record and ask folks to stop calling in reports about antifa. By then, millions of people had been exposed to the misinformation, and several dozen newsrooms had had to debunk the story.

The costs are very real. In Oregon, fears about “antifa” are emboldening militia groups and others to set up identity checkpoints, and some of these vigilantes are using Facebook and Twitter as infrastructure to track those who they deem suspicious.

Online deception is now a multimillion-dollar global industry, and the emerging economy of misinformation is growing quickly. Silicon Valley corporations are largely profiting from it, while key political and social institutions are struggling to win back the public’s trust. If we aren’t prepared to confront the direct costs to democracy, understanding who pays what price for unchecked misinformation is one way to increase accountability.

Combating smoking required a focus on how it diminished the quality of life for nonsmokers, and a decision to tax the tobacco industry to raise the cost of doing business.

Now, I am not suggesting placing a tax on misinformation, which would have the otherwise unintended effect of sanctioning its proliferation. Taxing tobacco has stopped some from taking up the habit, but it has not prevented the public health risk. Only limiting the places people can smoke in public did that. Instead, technology companies must address the negative externalities of unchecked conspiracy theories and misinformation and redesign their products so that this content reaches fewer people. That is in their power, and choosing not to do so is a personal choice that their leaders make.

from MIT Technology Review https://ift.tt/3lrf1Jx

via A.I .Kung Fu

Google and Facebook hate a proposed privacy law. News publishers should embrace it.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg testifies before Congress in 2018. | Alex Wong/Getty Images

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg testifies before Congress in 2018. | Alex Wong/Getty Images

California voters get a chance to shape internet privacy rules for the rest of the country in November.

While most of America is focused on the presidential vote, Californians have another important decision to make at the polls this November. They’re being asked to approve what will likely become the internet privacy law for the United States.

Proposition 24, also known as the California Privacy Rights and Enforcement Act of 2020 (CPRA), is supposed to expand a landmark California privacy law that passed two years ago; there’s a good chance Californians will approve this one, too. It’s framed as legislation that will better protect their privacy — in particular, sensitive data such as Social Security numbers, race, religion, and health information.

And while the proposed law technically governs the use and sale of data for Californians, California has an enormous impact on the tech industry, which means CPRA will become the de facto law for all of the US.

Which should sound like a good thing for most people. Among other impacts of the proposed law, it makes a point of protecting young people by mandating triple fines for infringements against consumers under age 16. It will allow consumers to restrict the use of geolocation data by third parties, effectively ending practices like sending targeted ads to people who’ve visited a rehab center or a cancer clinic. And it will fund the creation of an agency to protect consumer privacy.

For news publishers, though, any new data regulation can create problems, and news publishers already have plenty of well-documented problems. But I think the proposed enhancements will actually help the news industry.

Fighting the Google/Facebook duopoly

From targeted advertising to personalization, data does a lot of work online. Unfortunately, two companies dominate data collection and therefore digital advertising. One big question about any privacy laws is whether they actually create more advantages for Google and Facebook instead of leveling the playing field for smaller competitors.

We’ve seen this happen before. In Europe, which began enforcing a new privacy law in May 2018, big tech companies have been able to effectively neuter the law by implementing half-measures and exploiting loopholes while enforcement lags.

The good news for consumers and news publishers alike is that CPRA seeks to close any loopholes in the previous privacy law the state passed two years ago.

For starters, the law is supposed to more clearly limit data collection and use for third parties — companies you don’t expect to get access to your data when you visit a news site — while allowing publishers to continue to use data they generate on their own sites.

That makes sense. As we have noted for years, consumers generally expect an app or website to collect data about them to help improve the service, recognize them as return visitors, or to recommend content. But they don’t expect unknown third parties to collect data about them to build profiles and serve targeted advertising on unrelated sites or apps.

That unbridled data surveillance by some big tech companies outside of their own user-facing services — that is, Google and Facebook’s ability to track you even when you’re not on their properties — has undermined consumer trust in the entire digital economy. Giving consumers the ability to control their own data should help restore some of that trust.

Privacy and subscriptions can work together

News publishers are also increasingly interested in trying to sell subscriptions instead of relying on digital ads. CPRA can help there by letting publishers offer subscriptions to consumers who opt out of having their data shared with other parties.

Some CPRA critics think this provision puts a price on “privacy.” I would argue that it gives news publishers the flexibility to decide on their own business model, and gives consumers an opportunity to understand how content gets funded. If they do not find it compelling enough, they are likely to seek out a competitive news service elsewhere. News publishers feel this tension every day. That’s why I think they will see healthy competition for consumers at various price points.

Third parties and liability

Lastly, and maybe most importantly, the CPRA closes loopholes that could be exploited by big tech platforms. One aspect of this is what we’re calling “the switch language,” which clearly aligns the obligations of third parties to serve the interests of consumers. It notes that when a consumer exercises their opt-out rights and a publisher passes their choice along to all the companies with which it works (third parties), those companies must stop reusing that consumer’s data for any other purpose. This essentially forces those companies to revert to the role of a service provider. The “switch language” also prevents any wiggle room by not allowing contracts to override this requirement. As publishers experienced in Europe, platforms like Google and Facebook often use their unbalanced negotiating leverage to force publishers to sign over these data rights, so this section is hugely important for individual publishers that do not have the leverage to force Google or Facebook to stop mining data off their properties.

Finally, CPRA clarifies that publishers are not responsible for third parties that violate the previous section as long as they do not have actual knowledge of the violation. Taken together, these provisions reflect a thoughtful understanding of how data flows in the digital economy. They also put the onus squarely on big tech companies to tailor their data collection practices in accordance with consumer preferences.

Privacy laws are imperfect yet unavoidable

CPRA isn’t perfect, but it’s well-intentioned. And while you might hear tech giants warning that it will hurt publishers, you should consider the source of those warnings, and the motivations behind them.

Consumer expectations are evolving; policy, and our industry, must follow. Yes, there may be some short-term problems as advertisers get used to working with less data and lower the price for the ads they buy. But those playing the long game will be prepared for a world where more value is placed on publishers’ direct relationships — and consumer trust.

Jason Kint is the chief executive of Digital Content Next, a trade association that represents digital content companies, including Vox Media.

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

from Vox - Recode https://ift.tt/2GqglNL

via A.I .Kung Fu

A China-Linked Group Repurposed Hacking Team’s Stealthy Spyware

from Wired https://ift.tt/3nlW1xs

via A.I .Kung Fu

Profile of Singapore-based Sea Limited, an operator of online gaming, commerce, and financial services, whose market cap has quadrupled in 2020 to over $70B (Kentaro Iwamoto/Nikkei Asia)

Kentaro Iwamoto / Nikkei Asia:

Profile of Singapore-based Sea Limited, an operator of online gaming, commerce, and financial services, whose market cap has quadrupled in 2020 to over $70B — Gaming and e-commerce firm will ‘not compromise growth potential,’ says CEO — SINGAPORE — When Apple founder Steve Jobs gave …

from Techmeme https://ift.tt/30wNNca

via A.I .Kung Fu

The Haunting of Bly Manor review: A worthy follow-up to Hill House - CNET

from CNET News https://ift.tt/3nk0ZL9

via A.I .Kung Fu

Sunday, October 4, 2020

Gay men hijack Proud Boys Twitter hashtag with messages of love, pride - CNET

from CNET News https://ift.tt/3nl4GjN

via A.I .Kung Fu

Can a BBC reporter fool a face mask detector?

from BBC News - Technology https://ift.tt/2GBYYJw

via A.I .Kung Fu